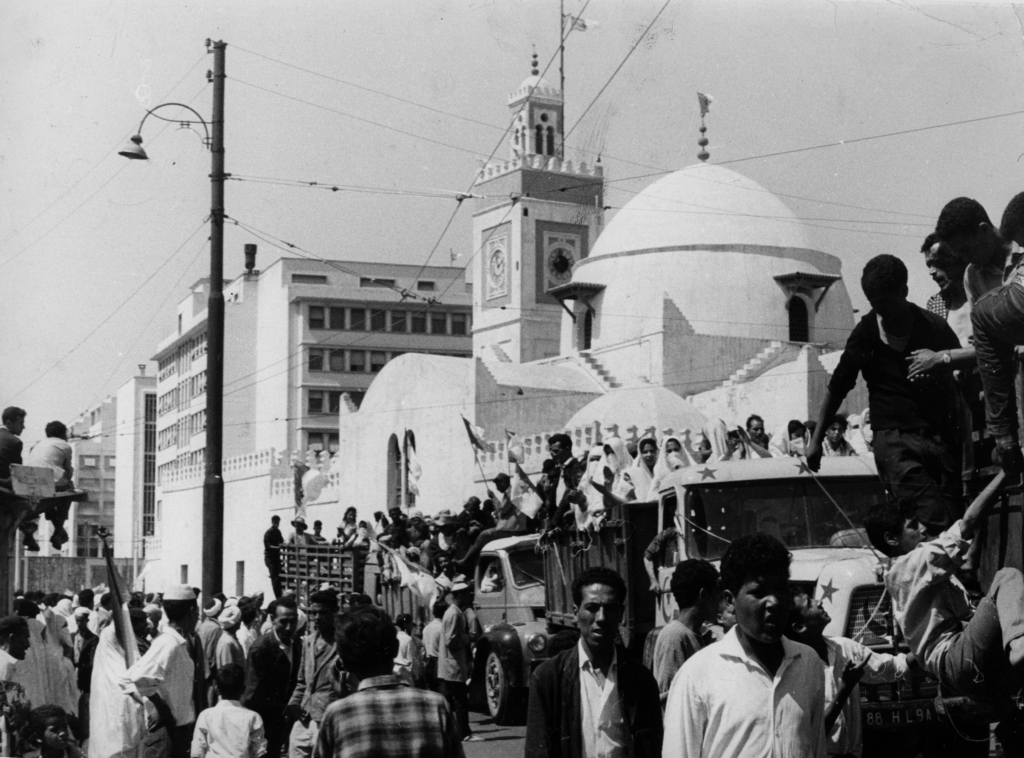

Independence was celebrated,

on the same date and at the same site,

upon which, one hundred thirty-two years earlier,

on July 5th 1830

the French invaded Algiers.

Looking at Muhamad Kouaci’s photographs

of the excited and cheerful crowd,

we get a clear sense

that the movement is gravitating forward,

toward the place

where official announcements will be made.

We see people determined

not to be left behind

or alone.

They all walk, singing and dancing

in the malleable choreography of

a flock.

However, when looking carefully,

members of the crowd often appear to morph into spectators

seeing a mirrored reflection of their independent selves

in the bodies and faces of others around them.

Members of the crowd are neither moving forward,

nor blocking the movement.

Rather they are attuning themselves to others,

learning how others are interpreting

and experiencing

the meaning of the day.

Everywhere it is the same.

People are taking time to be with others,

inventing their place among them,

appreciating how others

skillfully stretch the Euclidean space

so that they will not be

left out.

These are not individual acts.

Look, count how many hands and legs

work together,

in order to get

one person

on top of one truck.

They all know where they are heading.

They all perform the poetic justice

of ending the colonial era

at the very site where it began.

Allow me to refrain from calling this place

by its name right away.

Neither will I call it by the new one

that the nascent independent state

gave to it –

four months after these photos were taken.

Bear with me a little longer.

I want to share with you

the circumstances under which this site emerged

as a stage for political self-determination

and an object of political desire.

It could not come into being

without the onto-epistemological violence

that the French inaugurated

at this very site,

in the heart of the city of Algiers.

If you have any doubt about

the nature of this violence,

I’ll quell your confusion:

destruction and construction form its ontology,

taxonomy its epistemology.

In a matter of weeks,

Algiers stopped being the same.

It was made unrecognizable to its inhabitants.

All the means of violence perpetrated against it

were justified by the one goal

set by the French,

in the service of the French:

making Algeria French.

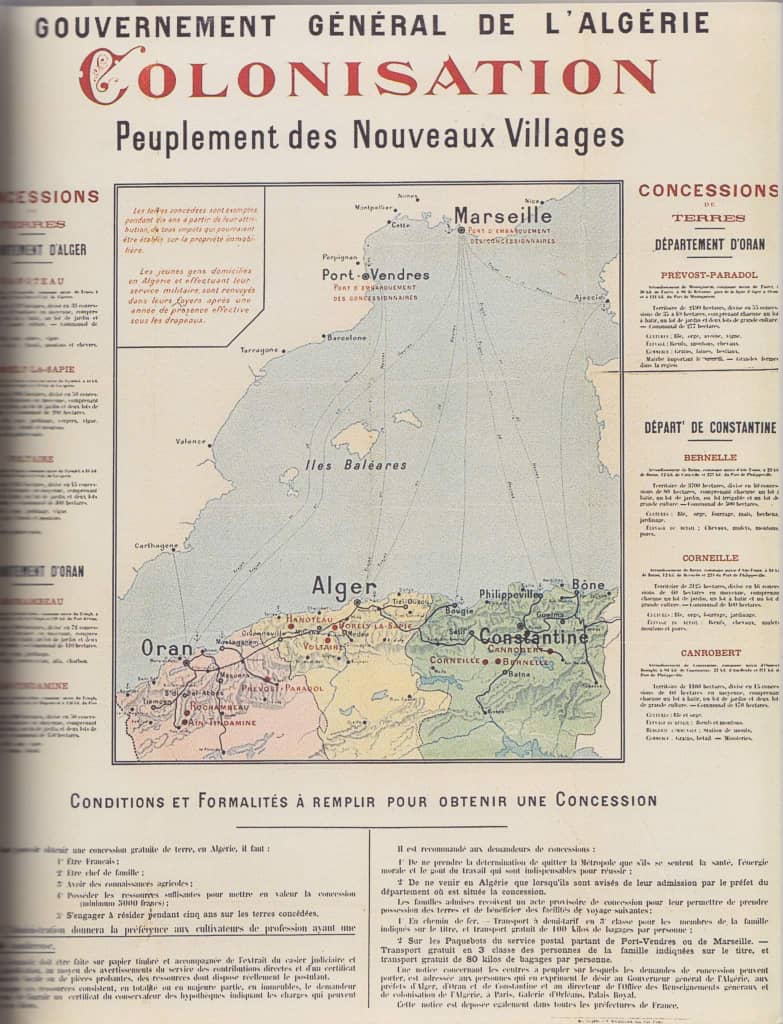

Frenchmen and Europeans

were invited to the city.

They were given lands, property,

and a carte blanche

allowing them to use their talent and creativity,

as well as their entrepreneurial skills,

to come up with their visions of a French Algeria.

They were welcome to use

in-house resources

to realize their dreams.

Librarians,

architects,

painters,

engineers,

archivists,

draftsmen – and, soon after, photographers,

librarians,

scientists,

archeologists,

physicians – and, soon after, psychiatrists,

and the list is long…

And the indigenous?

They had to acclimate,

to the foreign place

that grew out of their soil.

This place ‘unhomed’ them in their homes.

Some of the creative minds,

who came to build a French home in Algeria

(made of Algeria),

are still celebrated everywhere in France.

They arrived with the first military boats,

already possessing the tools and instruments

they needed

to make their ‘important cultural work’ possible.

They were invited

to build Algeria,

a place where,

according to their studies and observations,

there were

no civil status records,

no marriage contracts,

no identifiable family names or patronyms,

no museums,

no libraries,

no municipalities,

no voting system,

no public education,

no grand boulevards,

no post offices,

no archeological digging sites,

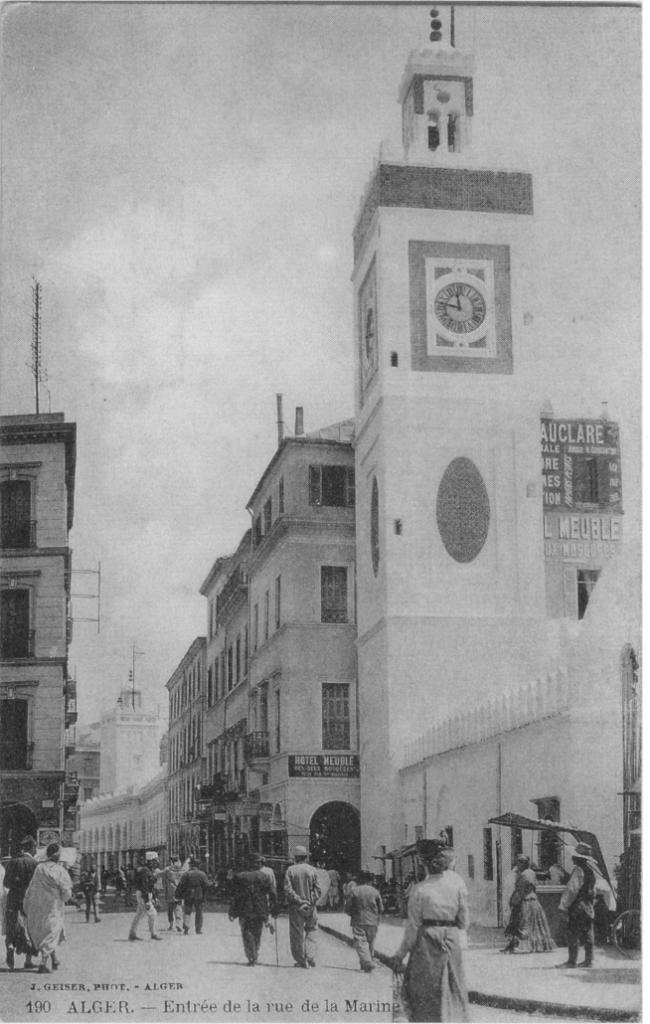

no tower clocks,

no physiognomic science,

no taxonomy of people nor their objects,

no punch on precious metal jewels,

no history,

no repertoire of forms

that allowed one to police

the authorship and ownership of crafts and possessions,

no discrete worship buildings,

that allowed one to determine

who belonged where

and who was ‘unruly,’

no public squares.

What they found

upon their invasion,

was illegible Kasbah.

Thus, with no further ado,

they started their work.

Until their departure

132 years later,

with zeal

they turned over almost every stone,

and built the institutions listed above,

and more.

They planted them in every city across Algeria,

so that their absence,

rather than presence,

would seem abnormal.

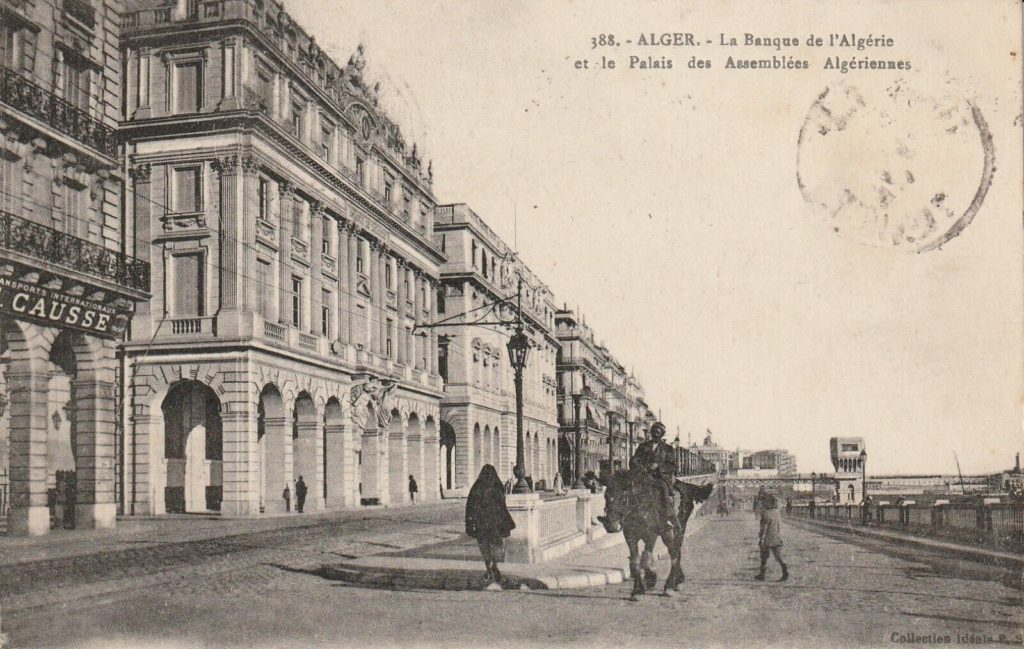

Thus, each military barrack,

each police station,

each municipality,

each bank,

marked another step on the indigenous

path to progress

that was paved with colonial universal forms,

without which (modern) life

couldn’t go on.

As the end of the colonial regime was approaching,

instead of

restituting some of what they took,

asking the indigenous for forgiveness,

or offering repair,

the French sought to take more,

from natural resources to works of art,

from documents to gas.

And yet, the worst part of their

onto-epistemological violence

did not consist in what they took,

but rather in what they left:

these colonial institutions,

which were made of their imperial democratic

political concepts and practices,

and accumulation of transgressions and violations,

which had already materialized in space.

Their seemingly innocent presence

in post-colonial Algeria

was perceived as a political promise:

once occupied, inhabited and operated

by the liberated colonized,

they could cease to function

as colonial state apparatuses

and serve as the building blocks

of an independent Algerian nation.

These apparatuses, however, were in fact,

the political curse of post-independent Algeria.

Some understood it earlier,

others later,

or maybe, it was only after a while,

that they were willing to admit it.

This curse is irreducible to individuals’ acts,

it is rather imbibed in the infrastructure of the colonial state,

which, in the wake of independence,

was not dismantled.

Algerian liberation was not hijacked post-independence.

It is useless to look for a point in time

in which the project of independence took a turn–

1965, or 1969, or 1975.

The failure of the post-independent state

is rather innate to a project of independence

that subordinated aspirations for decolonization

to a desire for a sovereign nation state.

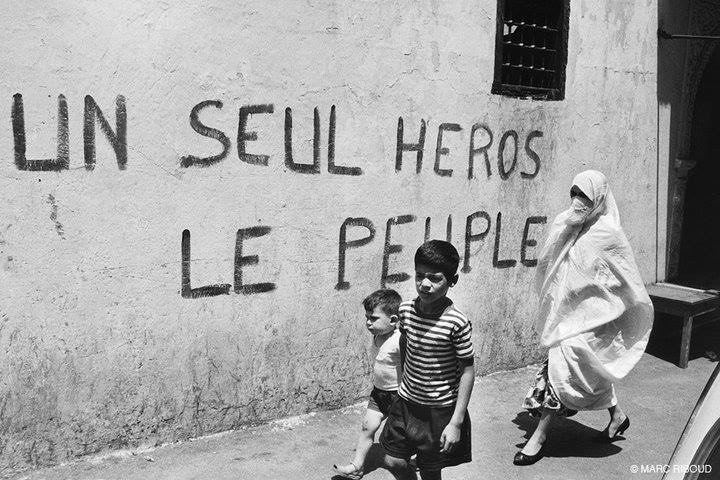

In this state it was not the people

who were conceived as the heroes of independence

but a manufactured body politic

from which undesired Algerians could be and were removed.

These institutions, some of which are commonly cherished –

museums, archives, libraries or public education –

were viciously crafted through

one hundred thirty-two years of plunder and forced assimilation,

ninety-two years of forced naturalization of one segment of the population,

eight years of intense war, and

almost two years of exhausting negotiations.

Independence, however, was not achieved

through the decolonization of any of these institutions,

nor did it create an opportunity to attend to colonial crimes,

wounds, injuries, damages, disorders, or syndromes.

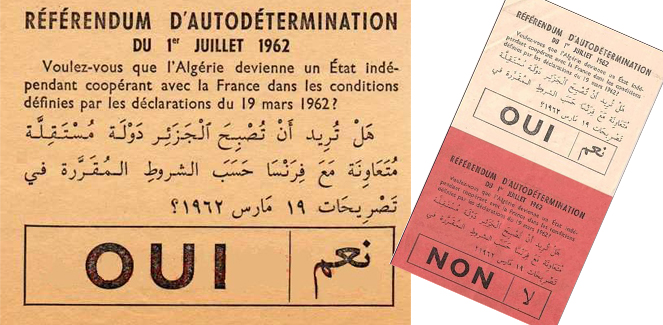

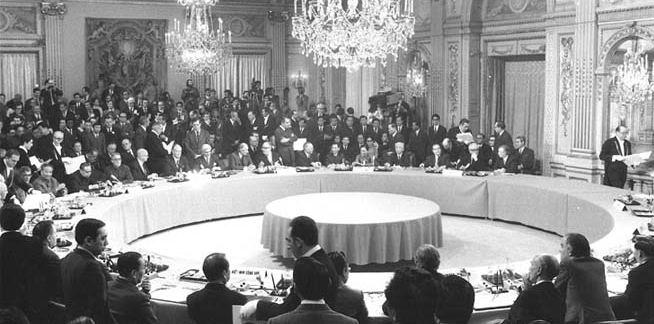

During the diplomatic negotiations in Evian,

the Algerian war (or revolution) was concluded

with a cease fire,

and a binding accord between “two sides,”

over the transfer of sovereign power

from a settler state to a nation-state.

The negotiations compelled the Algerian side

to “subscribe unreservedly”

to the secular principles of

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The relatively long negotiations were

like a long rehearsal,

wherein the Algerians had to make

this French revolutionary language theirs,

the same language which had sparked the French Revolutionary wars.

At the morrow of their 1789 Revolution,

the French were convinced that their conceptions

of freedom, rights and membership in the political community

were the ultimate best,

and they were ready to implement such ideals

wherever they could.

The result was the destruction of other cultures,

the replacement of such cultures’ centuries-old

politico-religious formations

with those of the French,

and the extraction of much of their resources,

which were used to finance the newly gained

French territories and empire.

These events marked also the beginning of the destruction

of the Jewish Muslim world.

The independence of Algeria

was its swan song.

The Evian negotiations imposed

the foundation of a secular democratic state,

in which and by which

many were not included or protected.

French statesmen and the

soon-to-become-Algerian statesmen

had not necessarily agreed upon

the composition of the body politic of such a state.

Rather, they conceded about its malleable nature

which would take form according to sovereign power’s interests,

and would be determined by the sovereign’s right to declare

who belongs where and who should be displaced.

The Jews and the harki

were among the immediate victims

of this transfer of power.

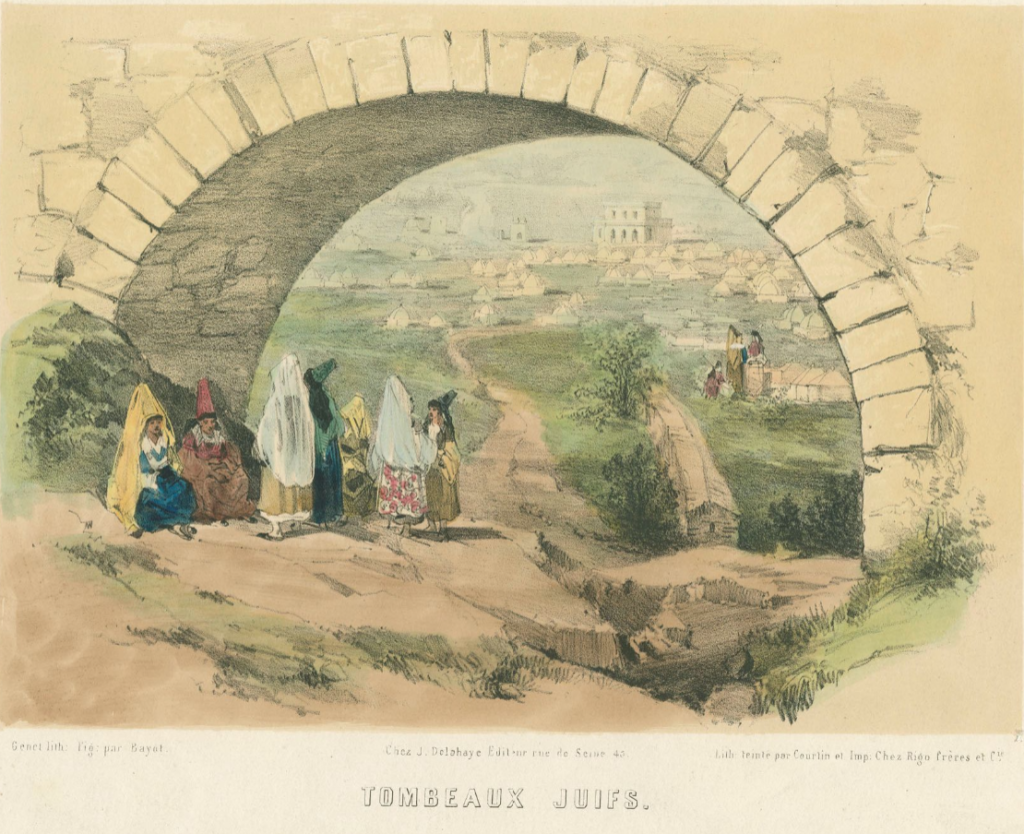

Before 1830, there was no question

that Jews were part of the Muslim nation

and were under its protection,

sheltered within the category of dhima

which rendered them “protected persons”

according to the Islamic law.

With independence, however,

Jews were revoked of their place

in the Algerian secular state

and Jewish Muslim life in Algeria,

which was as old as Islam itself,

was brought to its end.

With the absence of Jews from these discussions

between Christian French and Muslim Algerians,

the two “sides” of the negotiations in Evian,

a shared colonial understanding of the body politic – which excluded Jews –

took shape.

At the moment of Independence,

most of Algeria’s 140,000 Jews,

whose fates were even not discussed amongst these two sides

as they were assumed to be “Europeans” –

that is, embodiments of their colonial reformation –

were already gone.

During the months of negotiation,

some leaders of the FLN sent the Jews

a handful of confusing messages.

Jewish community members could not disentangle

these messages from the numerous violent attacks they were subject to at the same time.

The Jews’ absence was normalized,

like that of other groups subjected to forced migration,

provoked flight

and population transfer

in other places.

Such processes that contribute to formation of the imperial nation-state

are presumed to be the indispensable price paid for

the nation state’s birth.

And thus,

the disappearance of the Jews from Algeria

was an event that also disappeared from the

history and memory of Algeria.

Making the Jews disappear,

was one of the inaugural acts of

onto-epistemological violence

exercised by the French.

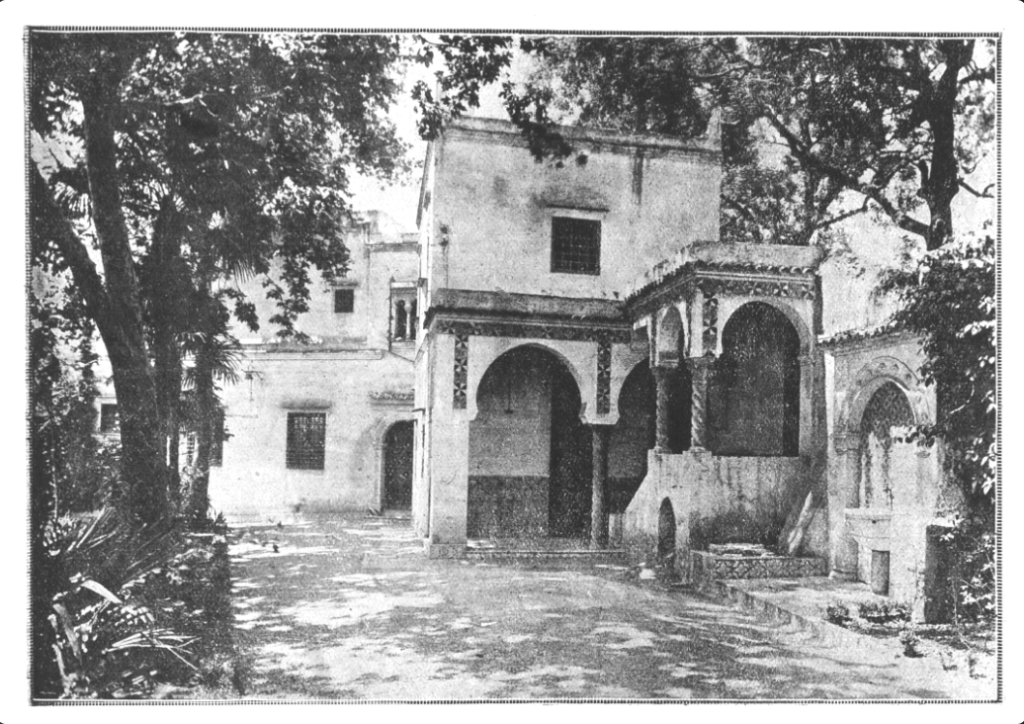

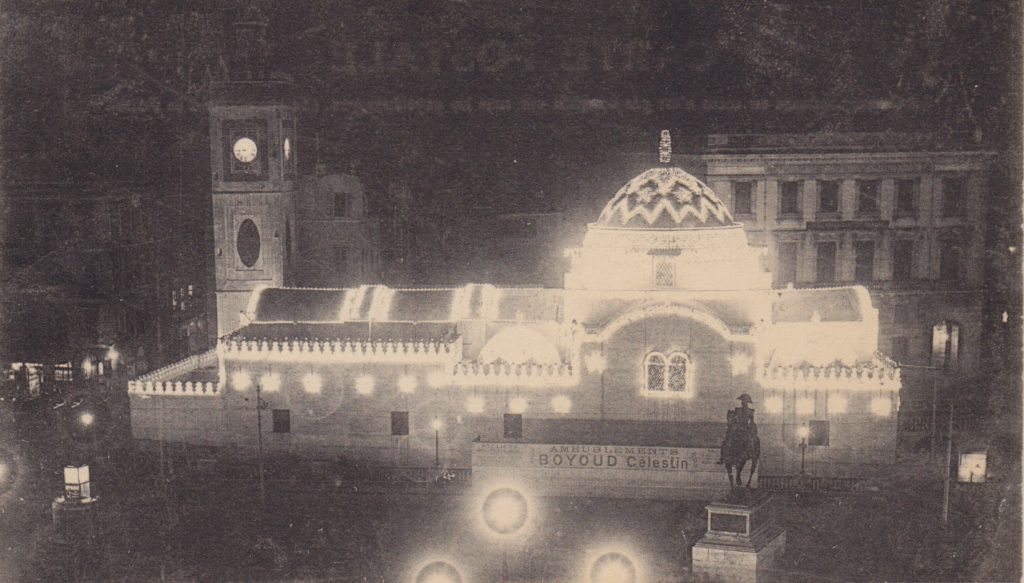

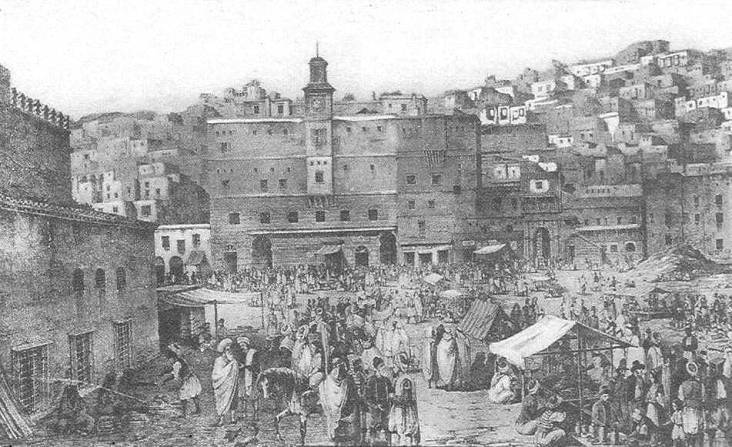

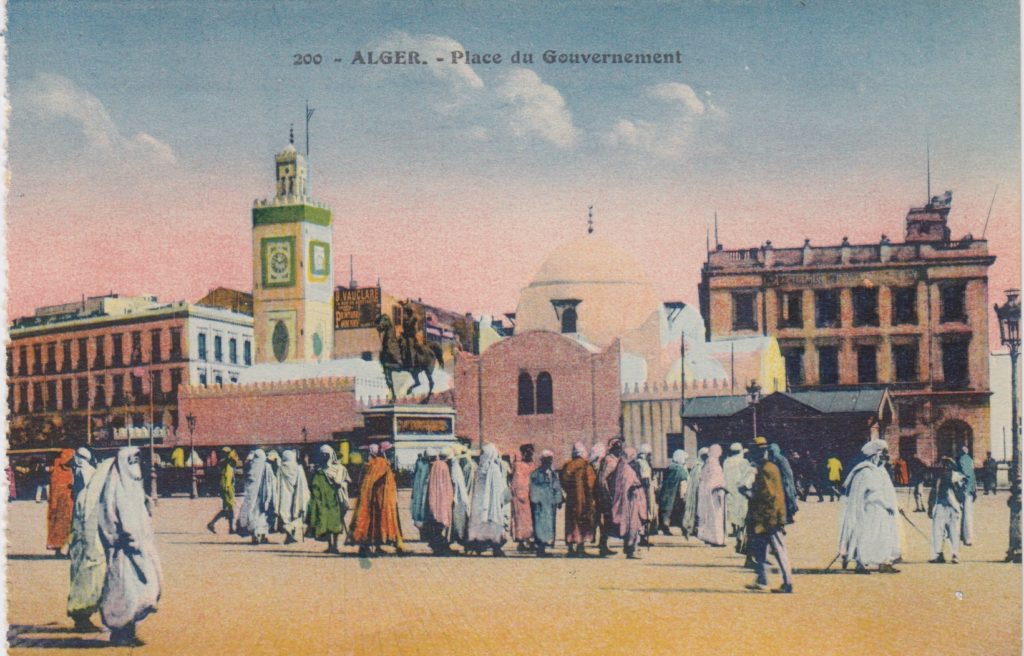

Let’s return now to the site of celebration.

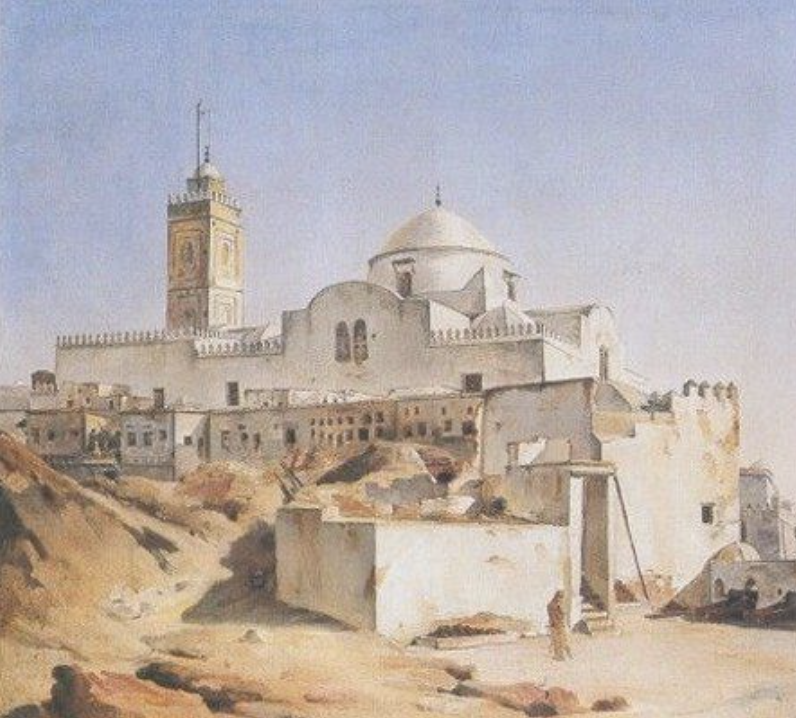

Look with me toward the foot of this hill.

On the left side, relatively close to the sea,

do you see the white mosque?

Unlike the other mosques that were demolished,

this one, in a certain way, was saved.

But what was saved is only the building itself,

while its existence prior to the invasion

was never as an isolated building.

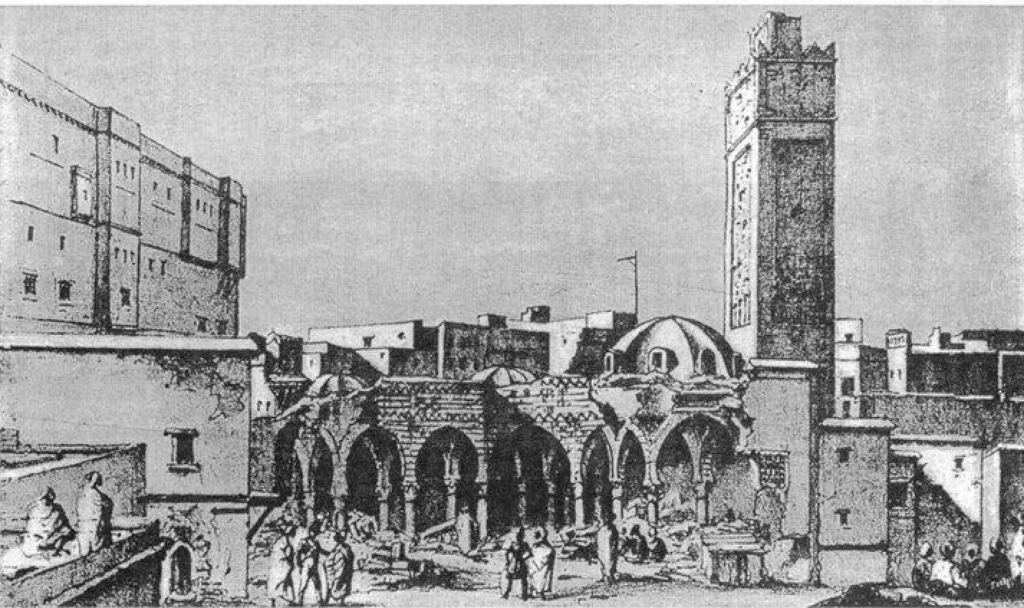

Here we see it displayed, as if it were on a pedestal,

upon the roofless white cube called ‘the square.’

But let’s not be confused by the language:

this ‘square’ was first posed

like a pall over the imperial violence

that turned the many buildings

which once formed the mosque’s entourage

into ruins.

It allowed the mosque to become an iconic structure.

Our Jewish ancestors’ gaze on this mosque

was different than ours.

It was not mediated by the wide field of vision

opened by the square

that invites viewers to look at it

from the outside and from a distance.

Rather, their gaze was part of their urban epidermis.

They did not abide by the dictates of

the modern secular phantasy of the “public space”

that invite us to judge

the mosque’s aesthetic value

in order to affirm its religious one.

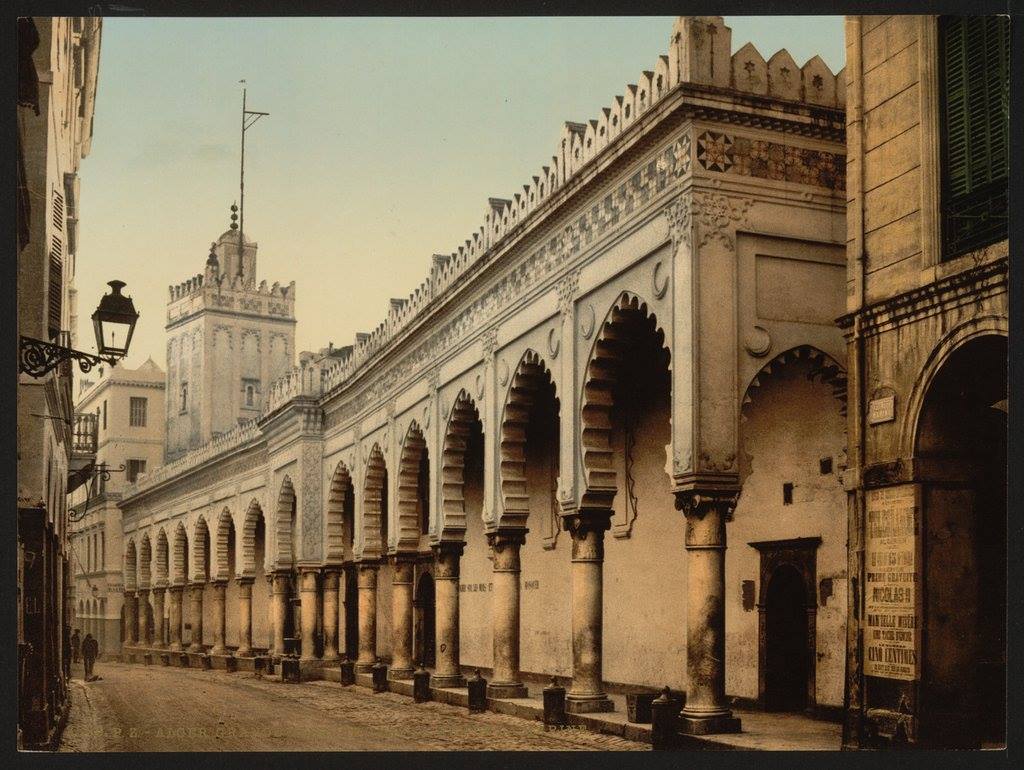

So here we are, in the Place du Government,

which symbolically changed,

during a military march carried out

four months after independence,

into the Place des Martyrs.

The violence done to the mosque

is somehow more evasive

and difficult to pin down

than that which is typically involved

when sites of worship are physically destroyed.

In a city in which Muslims and Jews

lived and worked together

in a close and packed environment,

sites of worship had a variety of

sensorial, material, cultural, social and spiritual

features and functions.

Such features and functions exceeded

those that could be categorized

by the colonial religious taxonomy

imposed by the French,

which sought to disentangle Jews and Muslims

by denying and destroying

the spaces in which

they practiced

their shared religious traditions.

In order to turn that mosque into

a white object on a plinth

and to endow it with a fixed meaning,

one that communicated the exclusive

‘Muslim’ provenance of the city,

hundreds of other sites of worship,

houses, ateliers and stores

to which it was connected through shared walls and paths

were demolished.

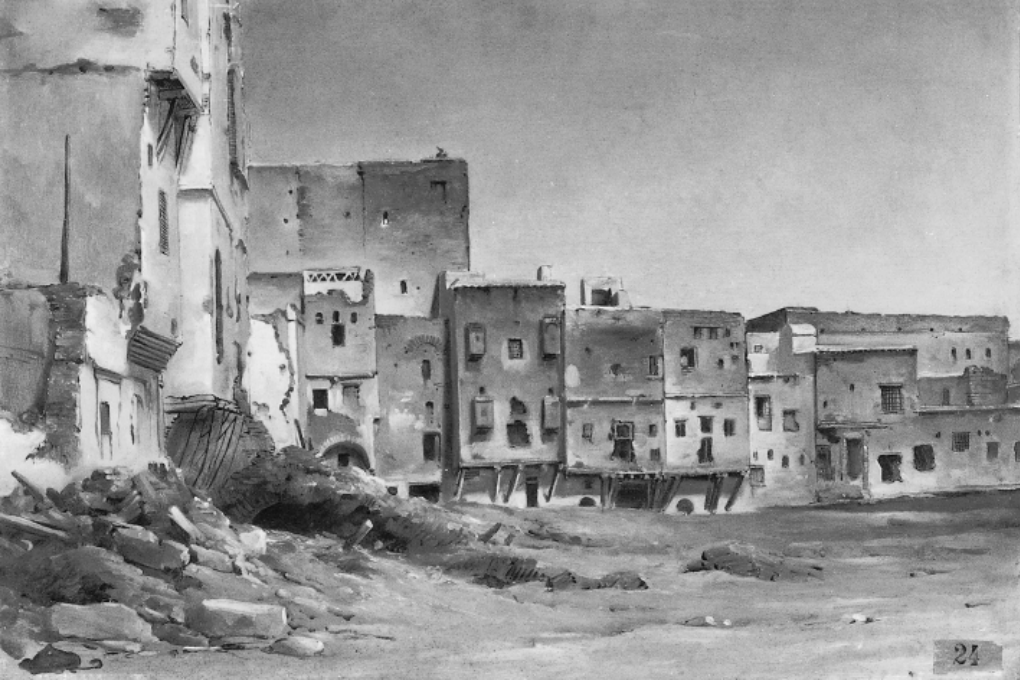

Some piles of rubble and sand

were recorded by French artists,

who came to Algeria to seek inspiration from its local colors,

and to make a career

by depicting these ruins

as well as what replaced them.

As a result of the destruction,

people lost the material and symbolic rights

they once held within this urban tissue.

They lost their shared history

and their sense of belonging

that was once anchored in this now-demolished space,

which was defined by the overlapping co-existence

of Jewish and Muslims craftsmen and their social formations.

After the destruction,

only from the high angle from which this photo was taken,

at the top of the Kasbah,

an image of the reality of these intermingling lives

could still emerge,

and this image could emerge only as a perspectival illusion.

When we get down the hill,

the illusion of the entangled mosque disappears,

and we encounter the results of the French invasion.

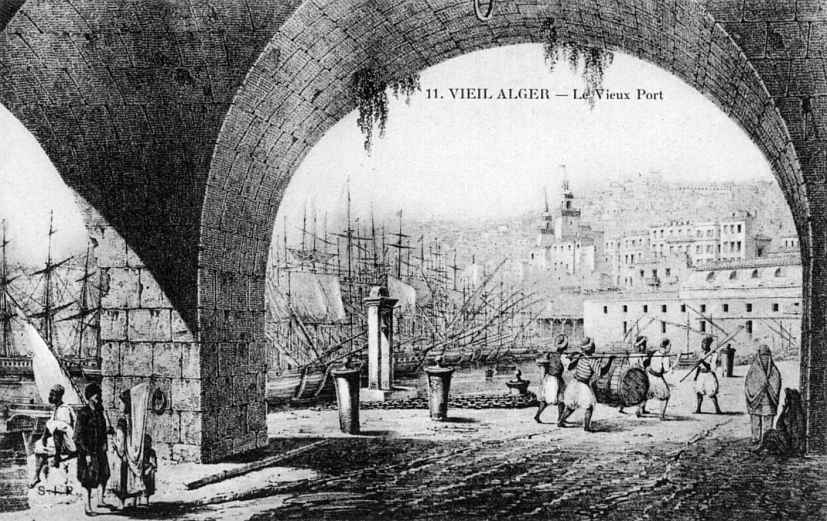

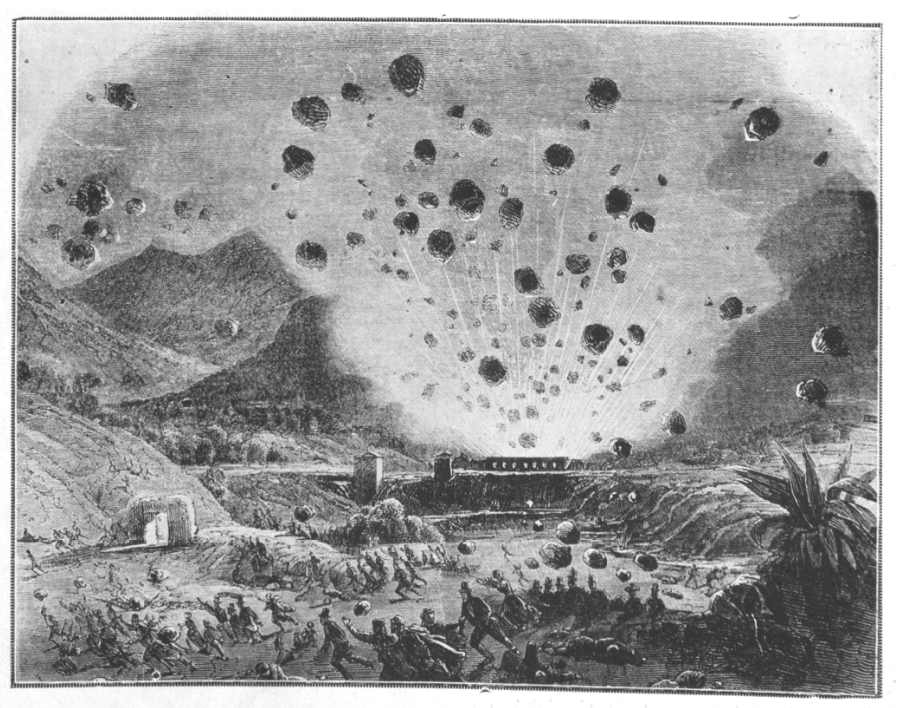

On July 11th 1830,

only six days after the invasion of Algiers,

Jews and Muslims together

were evacuated from the city.

And the destruction of the

heart of Algiers,

the center in which centuries of knowledge and know-how

were elaborated and transmitted across generations, began.

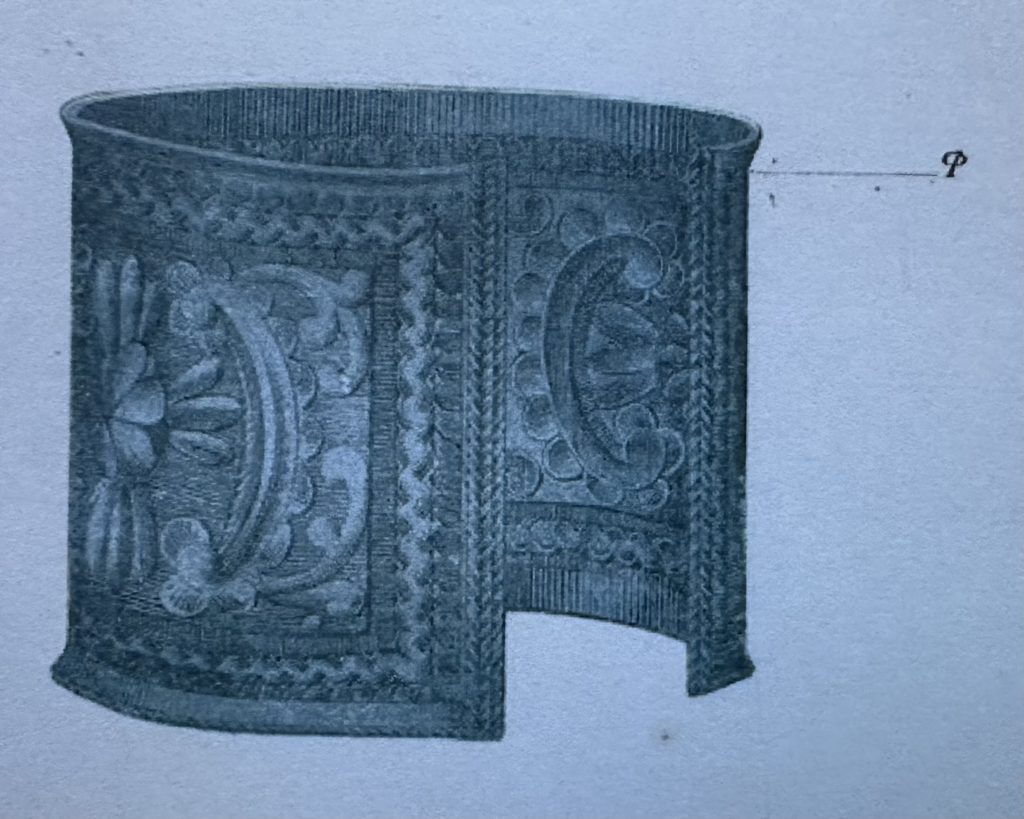

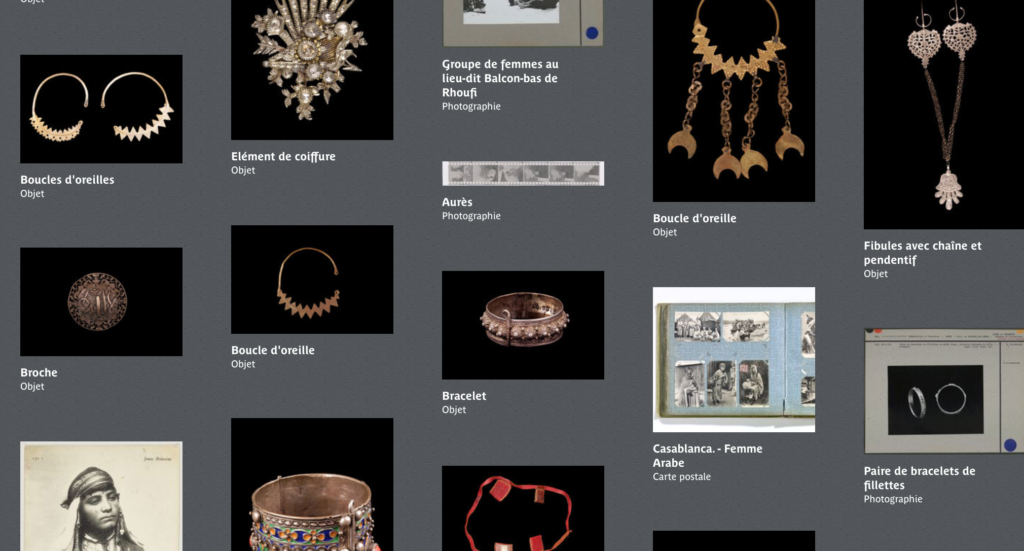

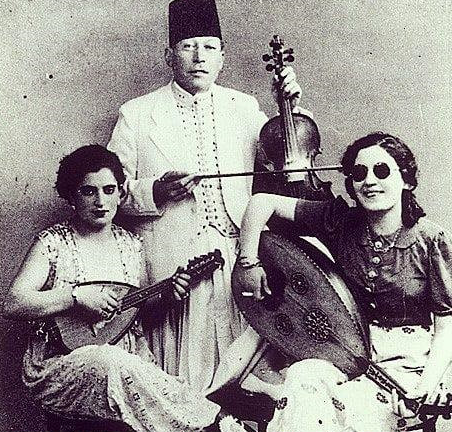

The ateliers of hundreds of Jewish jewelers, those of

different fabric dyers,

bracelet makers, book binders, illuminators,

were all destroyed.

The craftsmen, who,

until the conquest, had been members of guilds of peers,

had supported and helped each other in difficult times,

and had shared their affluent orders in prosperous times,

were now thrown into a competitive capitalist market

in which they had few chances to succeed.

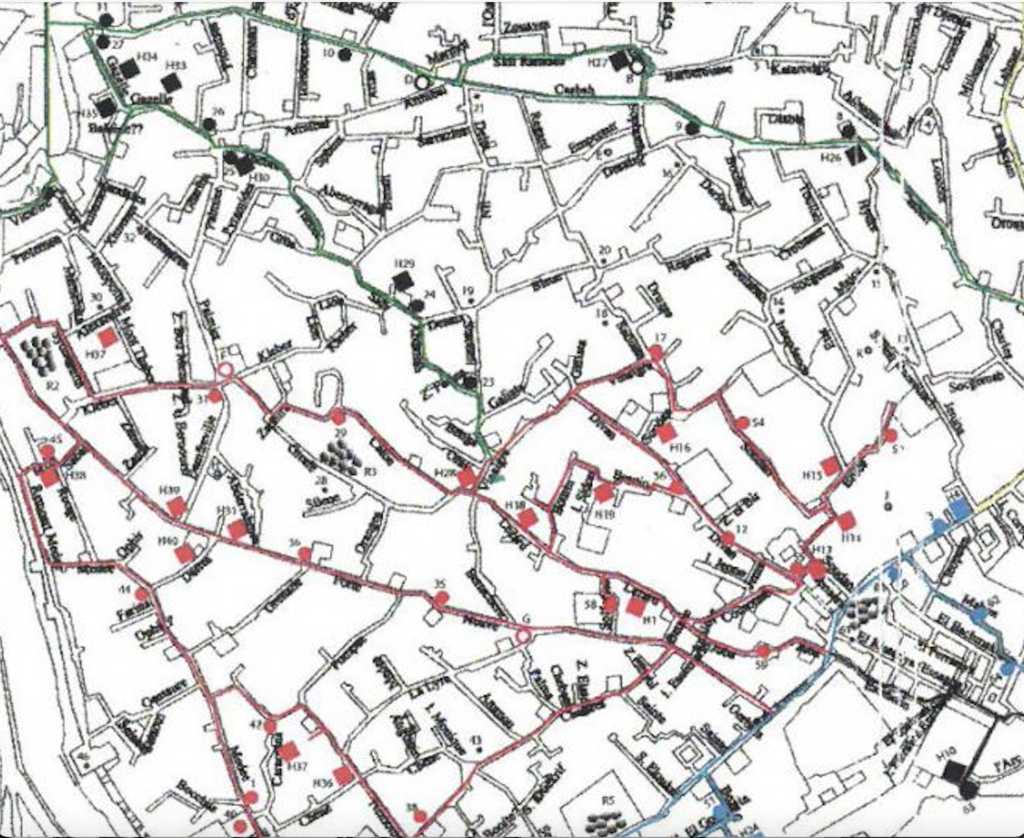

In order to create the square, the Kasbah’s lower slopes

had to be flattened and leveled,

the remains of the houses had to be carved out

and the semi-ditches that this created had to be filled.

Once the mosque was broken off,

isolated and whitened,

the French could display it as

an object of their choice and taste.

In other words, the same mosque that

they were about to destroy for its lack of value

was reborn as theirs.

They transformed it into an object of their choice and admiration

of their connoisseurship and engineering skills,

of their careful preservation methods,

of their scholarship and art.

And thus, they dealt with it as a source of their enrichment.

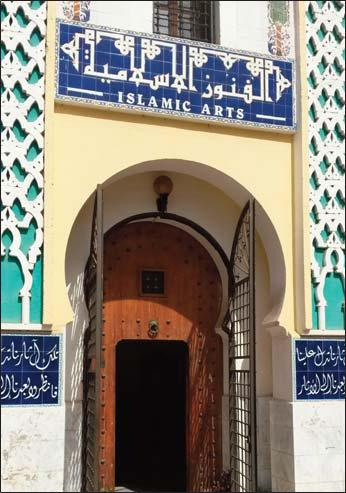

Self-appointed as the guardians of Islamic arts,

they could now teach its value and history

to the indigenous who,

in their eyes,

neither properly valued it nor knew how to take care of it.

Over the course of 132 years

the French had literally stolen

our ancestors’ livelihood.

Our ancestors became the props, the tokens and the laborers

of lucrative French businesses,

of French scholarship, literature, museums, connoisseurship and art.

When this clock struck

on Dar-es-Sultan-el-Quedima,

said Abd-el-Kader,

“the infidels will be the masters of the country.”

He anticipated the disastrous campaign of secular conversion

and refused to surrender to the French.

Not so long after,

the clock was embedded into this building,

and when this one was destroyed

it was affixed on the minaret of the Djamâa el Djedid.

Our ancestors worked in small winding alleys

and upon the main streets,

which were named after guilds of craftsmen –

the jewelers or the dyers.

These guilds’ formations of self-rule could still serve as

one of our political models for decolonization.

However, this amputation of the urban landscape

destroyed the communal existence and self-understanding

of my ancestors as Muslim Jews,

which was immersed in a shared culture for centuries.

The demolition of this whole neighborhood

cut off our ancestors’ access to their material and spiritual resources.

It thus inaugurated one of the major projects of the colonial state:

the “transference of wealth

from one ethnic group to another.”

In the process, the French removed the Jews

from what they reshaped as

solely a Muslim culture

in a European city.

Algerian wealth, excluding lands which the Jews didn’t have,

was therefore not transferred from Muslims to the French,

but from the indigenous – that is, both Muslims and Jews – to the French.

Look at this square and see

how this pristine binary was invented.

From the incredibly rich environment

that was buried under this square,

only a single isolated building was left:

a Mosque.

This mosque was made an emblem of Islam.

And its preservation in the square

sought to signify the Muslim culture of the city,

as if the Jews were not part of the world

in which mosques were conceived, built, sensed and signified.

The exile of Algerian Jews was already written

in this square,

but we could still imagine our return

through reclaiming what is buried underneath,

or the jewels held

close to women’s bodies.

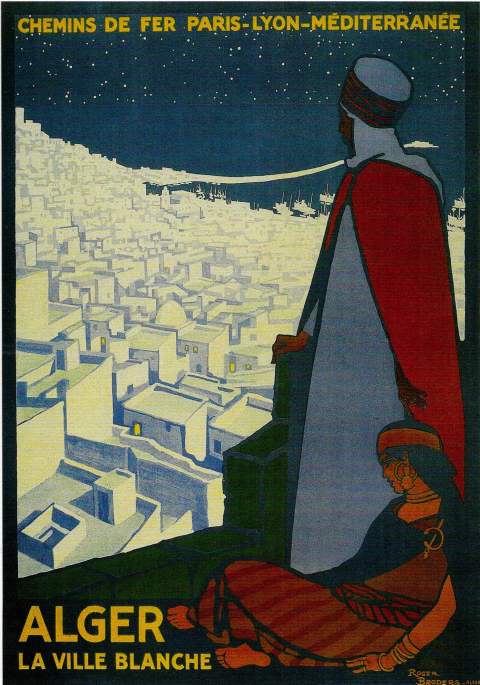

European tourists, settlers and artists

were attracted to Algeria

for its charm,

and for the way it purportedly juxtaposed two civilizations:

that of the French and that of Islam.

“This contrast

bursts in the customs, languages, usages

and even the mode of constructions of habitats.”

Hundreds of different postcards of the square

were printed in huge quantities

and were circulated across the world,

solidifying the idea of a Muslim monoculture

from which the Jews were dissociated.

Much of our Jewish ancestors’ labor,

love, memories, blood, histories and hopes

were involved in building this

Jewish Muslim world.

Yet, in the 1830s, the French turned it into rubbles

and simultaneously reorganized Algeria

according to their terms.

They thus commenced the material and symbolic exile

of the Jews from their heritage.

Rejecting the names that colonial regimes

gave to various structures and sites

and reverting back to their pre-colonial ones,

are common gestures of decolonization.

Changing the name of this square

from Place du Gouvernment

to Place des Martyrs,

was an important homage to the martyrs of the war,

but it also marks a failure on behalf of the

newly independent Algerian state

to attend to the necessity of decolonizing

the infra-structure of the colonial political regime

that was not imposed in 1954

but rather in 1830.

This regime was poised against Algerian livelihood.

It attacked Algerian ways of life,

especially their engagement

in artisanal life,

essential to the way they cared for their shared world.

Reversing the onto-epistemological imperial violence

that is materializes in this square,

ought to involve

the recovery and repair of Jewish Muslim worldliness that is

buried under it.

Before the Jews were colonized by the French

and later by the Zionists,

they were defined by their professions,

and were, in fact,

the jewelers of oumma.

The temporary absence of the Jews

from the celebration of independence,

should not mislead us to believe that they will be absent from

the decolonization-still-to-come.

The Jews are still there,

in every pair of earrings,

in every bracelet,

in every necklace,

just as they had been for centuries.

In undoing the colonial taxonomization of

objects as Muslims,

we can notice the presence of the Jews,

see them again as part of the body of colonized,

and imagine the renewal of the Jewish Muslim world

as one of the necessary paths toward decolonization.